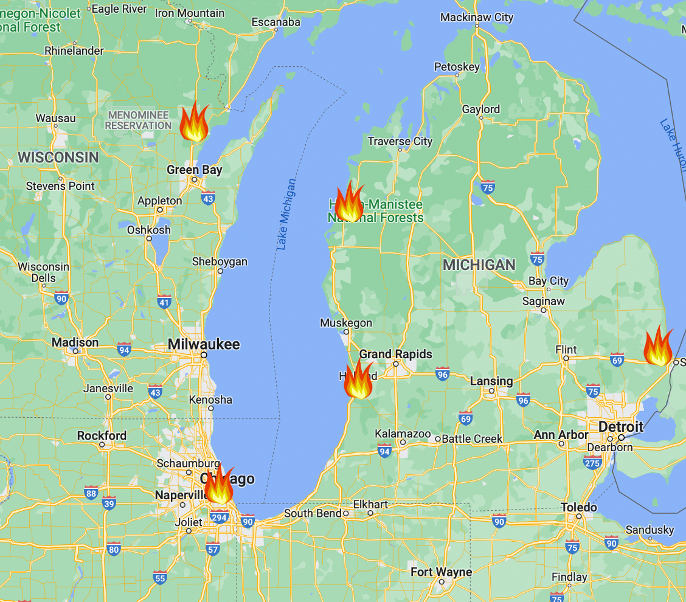

October 8, 1871 Fires

Most likely you’ve heard of The Great Chicago Fire, which happened on October 8, 1871. Probably the most famous fire in the history of the USA, it burned down the city of Chicago, which was the fifth-biggest city in the nation at the time.

In fact, calling it a ‘fire’ is probably an understatement. A more accurate description would probably be “giant ass city-leveling cataclysmic inferno.” It completely destroyed everything in its path, leaving only soot and smoldering piles of ashes.

Chicago History Museum

The city wasn’t just burned; it was flattened. Today, there are only 7 buildings still standing that survived the fire.

But did you know a separate fire, a fire that’s regarded as the most devastating fire in the history of the United States, happened on the exact same night?

Seriously. On the Exact. Same. Night.

200 miles to the north, the Great Peshtigo Fire destroyed 1.5 million acres of land in Northern Wisconsin and killed 2500 people on the night of October 8, 1871, 4x as many as the more famous Chicago Fire.

This fire was a monster. To understand the sheer size of the Peshtigo fire, bear in mind that the well-known 2018 fire that destroyed Paradise, CA, covered just over 150,000 acres. The Peshtigo fire was 10x larger!

And if you think that’s everything that happened on Oct. 8, 1871…well, Billy Mays has a few words for you.

There was a third absolutely massive fire in the Midwest that night. The Port Huron Fire burned down the town of Port Huron, Michigan and destroyed 1.2 million acres of land, nearly as much as the Peshtigo Fire, though it’s estimated that only 50 people died in the Port Huron Fire.

Crazy, right? 3 of the 5 most devastating fires in the history of the world, hundreds of miles apart, all occurring at the same time on the same night.

And if you think that’s incredible, Billy Mays is back with something else to say.

There were 2 MORE gigantic fires in Michigan that night. The Holland Fire leveled over 300 homes and other structures in the budding town of Holland, Michigan. And the Manistee Fire destroyed the town of Manistee, Michigan, and left thousands homeless.

That’s 5 massive fires. On the same night. At the same time. 100s of miles apart. It’s a simply incredible fact that’s been largely forgotten with time.

So what in the flying hell happened on the night of October 8, 1871?

THE WEATHER CONDITIONS

Some claim the weather conditions were the cause of this unprecedented rash of fires. The summer and fall of 1871 were some of the warmest and driest on record, and the night of Oct. 8 was extremely windy throughout the Midwest.

Plus, many structures back then were built from wood; even the sidewalks were wood.

This combination — heat, dryness, wind, and wood — created conditions that were ripe for the ignition and spread of fires. In fact, throughout the summer and fall of 1871, the Midwest had been plagued by a series of small fires, though each had been contained by fire departments.

Chicago itself experienced a fire on October 7, 1871, the very night before The Great Chicago Fire. This fire was the largest fire that had ever struck Chicago up to that point; newspapers dubbed it “The Great Conflagration.” Fueled by dry conditions and wind, this fire burned down 4 city blocks and structures including lumberyards, a paper-box factory, and cottages made of wood.

Chicago Tribune, October 8, 1871

4 city blocks being burnt down by a fire is no joke. Yet the 4 blocks burnt by Oct 7’s “Great Conflagration” was nothing compared to the 3.3 million square miles destroyed by the fire the very next night.

Coincidentally, Manistee, Michigan, was hit by a fire the very morning of Oct. 8, just a few hours before that night’s destructive fire. A passage in Mrs. O’Leary’s Comet by Mel Waskin describes this morning fire:

“The firemen worked all day and were relieved to see that, despite the wind, the fire did not spread. It was extinguished…Then at 9:30 pm, the same time that fire broke out in Chicago and Peshtigo, the fire alarm sounded again. To their horror, the people of Manistee saw a bright red glare in the western sky…This was a fire of new character, out of control. They wondered what was happening.”

So why was the Chicago fire on Oct. 8 infinitely more devastating than the fire on Oct. 7? Why were firefighters able to contain the Oct. 8 morning fire in Manistee, yet the fire that night raged out of control and devastated the town? And why were there so many massive fires throughout the Midwest on that night, some of which were more intense than anything this country had ever or would ever see?

Many believe something else contributed to the fires that night.

Something otherworldly.

THE COMET

One explanation for the widespread fires on Oct. 8, 1871, is that they were caused by a comet colliding with Earth that night. Those who’ve studied astronomy from this era have even pinpointed the comet they believe contributed to the fires: Biela’s Comet.

First discovered in 1826, Biela’s Comet caused worldwide panic in 1832 when it passed within twenty thousand miles of Earth’s orbit, one month before Earth itself had passed that point. Had the comet been slowed or slightly knocked off course in some way, there was worry that it could have collided with Earth.

Comic from the 1800s with the caption: “Inevitable impact of the Earth with Comet Biela.”

The Caledonian Mercury, Oct. 18, 1832

Every 6.6 years, Biela’s Comet would become visible as it passed Earth. These passings generated great worldwide attention; it was just as famous as Halley’s Comet back then.

On Biela’s passing in 1846, astronomers discovered something incredible: Biela’s Comet had split into two comets, which were traveling through space in parallel with each other. This ‘double comet’ was described as the astronomical sight of a lifetime.

“What can be the meaning of this?” Professor James Challis wrote upon observing the double comet. “Are they two independent comets? I incline to the opinion that it is a binary or double comet…But I never heard of such a thing…”

The reappearance of Biela’s double comet in 1852 was widely covered in newspapers of the time.

Liverpool Mercury, Sept. 21, 1852

The Times-Picayune, November 7, 1852

There was great anticipation for Biela’s return in 1859, but astronomers were left disappointed when they were unable to spot the comet as it passed Earth.

The same thing happened when Biela’s Comet was scheduled to pass by Earth in 1866 — they searched the skies, but no comet was found.

Where had the comet gone? Some speculated the comet had exploded or broken apart in deep space. But others thought that Biela’s Comet was still out there. And that, in six years’ time, right around early 1872, Biela would again return to Earth’s orbit.

STRANGE BEHAVIOR

Many believe that when Biela broke into two comets around 1846, the comet’s path through space was altered. Remember, Biela created worldwide panic in 1832 when it passed within 20,000 miles of Earth’s orbit, a month before Earth passed that point. All it would have taken was a slight change in trajectory for the comet to arrive earlier than its 1872 scheduled passing and collide with Earth on October, 8, 1871.

If that did happen, it could explain much about that strange rash of fires that night. Comets are filled with gases like methane and acetylene, highly flammable gases which can produce temperatures in excess of six thousand degrees Fahrenheit. The intense wind that night would have transported these lethal gases throughout the area, and the hot, dry weather in the Midwest made the area ripe for fires, as witnessed by the fires in the area in the days before Oct. 8.

These conditions combined with the lethal gases released by the comet could explain the unprecedented rash of fires that night, as well as some of the other strange phenomena accompanying the fires, such as…

INTENSE HEAT

The fires that night were no ordinary fires. Witnesses described heat that was unlike anything they’d experienced. Buildings that were considered fireproof like The First National Bank building and The Tribune Building in Chicago were reduced to smoldering piles of twisted metal and rubble.

A few passages from books written about the Oct. 8, 1871 fires describe this heat:

“The heat was incredible. Massive stone and brick structures literally melted before the astonished eyes of the onlookers. Six-story buildings blazed up and disappeared forever in five minutes or less.” —Mrs. O’Leary’s Comet, Waskin, page 105

“The most striking peculiarity of the fire was its intense heat. Nothing exposed to it escaped. Amid the hundreds of acres left bare there is not to be found a piece of wood of any description, and, unlike most fires, it left nothing half burned... The fire swept the streets of all the ordinary dust and rubbish, consuming it instantly.” —The Great Conflagration, Upton & Sheahan, page 119

“The prevailing idea among the people was, that the last day had come. Accustomed as they were to fire, nothing like this had ever been known. They could give no other interpretation to this ominous roar, this bursting of the sky with flame, and this dropping down of fire out of the very heavens, consuming instantly everything it touched.” —The Great Conflagration, Upton & Sheahan, page 374

DEADLY AIR

Survivors of the Peshtigo Fire described people dying from inhaling noxious air:

“Corpses were later found in the roads and fields: there was no visible mark of a fire anywhere near them, and their bodies and clothing were not burnt in any way. But they were undeniably dead…There was no mark of fire upon these people; they lay there as if asleep.” —Mrs. O’Leary’s Comet, Waskin, page 69

“A spectator of the terrible scene says the fire did not come upon them gradually from burning trees and other objects to the windward, but the first notice they had of it was a whirlwind of flame in great clouds from above the tops of the trees, which fell upon and entirely enveloped everything. The poor people inhaled it, or the intensely hot air, and fell down dead.” —The Great Conflagration, Upton & Sheahan, page 372

STRANGE ELECTRICAL ACTIVITY

It’s believed that comets trigger electrical discharges as they travel through space, and many odd discoveries found in the aftermath of the fire could be attributed to a sudden surge of intense electrical activity.

“We have in our possession a copper cent, taken from the pocket of a dead man in the Peshtigo Sugar Brush…this cent has been partially fused but still retains its round form and the inscription upon it is legible. Others in the same pocket were partially melted off, and yet the clothing and the body of the man was not even singed. We do not know any way to account for this unless, as is asserted by some, the tornado and fire were accompanied by electrical phenomena.” —Mrs. O’Leary’s Comet, Waskin, page 76

BURNING SAND

Survivors described being assaulted by red-hot sand that swirled in the air that night. No one knew where this sand was coming from, but this mysterious sand could be explained by a crashed comet, whose body is made up partly of sand.

Accompanying the firestorm and wind was a rain of red-hot sand. It was not clear to those eyewitnesses who survived their ordeal where this sand came from…There was sand on the beaches, but the beaches lay to the east, and the wind was blowing from the west and south. There was no sand on the floor of the forest or farmlands of Wisconsin.” —Mrs. O’Leary’s Comet, Waskin, page 78

People spoke of ‘a pitiless rain of fire and sand.’ —Mrs. O’Leary’s Comet, Waskin, page 76

The obstruction came from a steady stream of sand, which drove against their faces like needle points. —Mrs. O’Leary’s Comet, Waskin, page 97

FIRE BALLOONS

Survivors also described ‘balloons’ of hot fire that rained down upon the Midwest that night.

Many survivors described these great balls of fire falling from the sky. Round smoky masses about the size of a large balloon, traveling at unbelievable speed. They fell to the ground and burst. A brilliant blaze of fire erupted from them, instantly consuming everything it touched. It is possible that these fireballs were actually flaming masses of methane acetylene gas from a comet, ignited by their passage through the atmosphere. —Mrs. O’Leary’s Comet, Waskin, page 78

There was the story of the Lawrence family in Peshtigo, who fled to an immense, isolated clearing on their farm, which was several hundred yards from structures or trees.

When the fire came, rushing on all sides of them, it did not in fact touch them. But eye witnesses saw them die. A great balloon of fire dropped on them: father, mother and four children. They were incinerated in an instant. Almost nothing was left of them. —Mrs. O’Leary’s Comet, Waskin, page 78

There has never been a night like October 8, 1871. 3 of the most devastating fires in the history of the world happened simultaneously, hundreds of miles apart.

Did intense winds carry lethal gases from a crashed comet, which combined with fires and hot, dry conditions to create an unprecedented night of destruction?

Or is there another explanation for the fires that raged that night?

MISC. INFO

As noted previously, fires were much more common back in the 1800s. Boston was famously hit with a large fire a year after the 1871 fires.

A decade later, the area surrounding Hinckley, Minnesota was burnt by a fire that’s considered one of the worst fires the history of the USA.

But these fires were nothing compared to the fires of Oct. 8, 1871. The Boston Fire burnt down 66 acres of the city — a fraction of the 2,000 acres destroyed in Chicago the year before.

1894’s Hinckley Fire was a rural fire like Oct. 8, 1871’s Peshtigo Fire. But in terms of sheer devastation, the fires aren’t even comparable. Hinkley burned down 250,000 acres. Peshtigo destroyed 1.5 million acres. Even the Port Huron Fire of October 8, 1871, destroyed over 1 million acres.

The comet theory was first proposed by former Congressman Ignatius Donnelly in his 1882 book Ragnarok: The Age of Fire and Gravel. The book sold well but the ‘comet’ explanation wasn’t revived until 1985, when Mel Waskin released the highly-publicized Mrs. O’Leary’s Comet. Waskin was a creative director for Coronet/MTI Film & Video, who made science films for schools; those films you watched back in science class as a kid were most likely created by Waskin.

In 2004, a scientific paper from physicist Robert Wood further explored the idea that Biela’s Comet had caused the fires.

An enduring myth of the Great Chicago Fire is that it was caused by a lantern that was kicked over by a cow belonging to one Mrs. O’Leary.

It’s a cute story. But it’s been disproven many times over the years. In 1893, reporter Michael Ahren admitted that the ‘cow’ story was fabricated.

St. Louis Post-Dispatch, Feb. 24, 1927

Sumter County Journal, Feb. 24, 1927

Fifty years after the Great Chicago Fire, a committee was formed to investigate the cause of the fire. They concluded that Mrs. O’Leary and her cow weren’t responsible.

“…it has been positively established by a committee that Mrs. O’Leary and her cow had nothing whatever to do with the blaze.” —The Salina Evening Journal, Sept 21, 1921

In 1871, months after the fire, there was an official inquest into the fire and Mrs. O’Leary was even called as a witness. She claimed he was in bed when she received a phone call that her barn was on fire — along with two other barns that didn’t belong to her. A neighbor of the O’Leary’s, Catherine Sullivan, also testified that she saw the O’Leary’s barn and two others on fire.

Fire Marshal Robert Williams, of the main men tasked with battling the blaze, testified in the inquest as well: he said the fire at the O’Leary’s barn was “under control” and “could not have gone a foot further”…but as he and his men were about to leave the scene, he got a call: St. Paul’s Church, which was a full two blocks north, was on fire.

In 1997, Mrs. O’Leary (long deceased) was formally absolved by the Chicago City Council of starting the fire.

Further Reading

http://endoftheage.blogspot.com/2012/10/the-great-chicago-fire-of-1871-was.html

https://www.sott.net/article/148414-Comet-Biela-and-Mrs-O-Leary-s-Cow

https://thumbwind.com/2021/10/06/great-lakes-fire-1871/

https://www.alltopeverything.com/deadliest-wildfires/

https://sites.rootsweb.com/~mimanist/ManHist14.html

Books